Servaas Storm, a senior lecturer of economcis, has critically analysed the focus on nominal unit labour costs (ULC) taken by some economists in explaining the crisis of the European Monetary Union (EMU) (see here). “German wage moderation in this story”, writes Storm in his analysis, is according to those economists, “(mostly) to blame for the weakening of Southern Europe’s cost competitiveness as well as the large capital flow from Germany to the increasingly indebted and vulnerable Eurozone periphery.” Storm doesn´t completely deny the role of German wage moderation, but in his point of view it bears only “part of the responsibility for bringing about the Eurozone crisis”. Storm rather criticises the “single-minded emphasis on the importance of relative unit labor cost competitiveness” as “misguided”. However, what is science if not reducing complexity to one crucial factor or at least some important factors? But this is not the main point I want to raise here. The main point I want to raise is on a possible misunderstanding of wage moderation by Storm. There are definitely more interesting arguments in Storm´s analyses to question, but the question on what wage moderation or wage restraint is really seems to me the most relevant.

Storm writes:

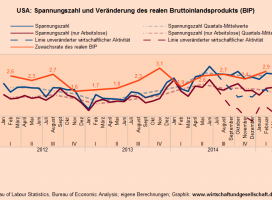

“…It is nevertheless true that Germany’s unit labor cost declined relative to those of the rest of the Eurozone (as Figure 1 illustrates), but this was not a result of wage restraint: It was completely due to Germany’s outstanding productivity performance: during 1999-2007 average German labor productivity (per hour worked) increased by almost 8 percentage points compared to the rest of the Eurozone, which accounts fully for the decline in Germany’s relative unit labor costs by 7.8 percentage points over the same period. It was German engineering ingenuity, not nominal wage restraint or the Hartz “reforms”, which reduced its unit labor costs. Any talk of Germany deliberately undercutting its Eurozone neighbors is therefore beside the point. …”

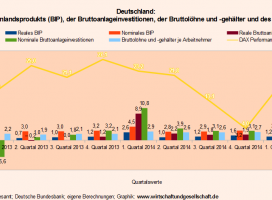

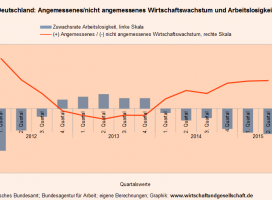

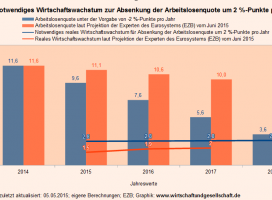

The fundamental misunderstanding of the meaning of nominal ULC taken by itself and for the EMU as well as for any monetary union or fixed exchange rate regime by Storm is in my point of view perfectly shown here. Storm relates the development of the relevant indicators (labour productivity, nominal wages, unit labour costs) in Germany to their development in the EMU as a whole (without Germany). However, this is not what actually matters in a currency union. What matters is that nominal wages in each single country of the EMU develop according to their country´s development of productivity plus the inflation target of the ECB to approach the ECB´s inflation target of “below, but close to two per cent”, meaning that nominal ULC would rise each year “below, but close to two per cent” in each country of the EMU. France, for example, followed that rule (from the beginning of the EMU in 1999 at least until the outbreak of the crises 2008/2009) and managed to meet the inflation target of the ECB. Germany did not, and the southern countries did not, too (only the other way around than Germany). The correspondence of wage development and productivity development plus the inflation target of the ECB is also important to balance domestic and foreign demand inside the currency union. The crucial point then is that it doesn´t matter whether Germany or any other country has an “outstanding productivity performance” or the opposite; the only thing that matters is that the development of nominal wages corresponds with the development of productivity – plus the inflation target of the ECB.

The whole confusion on that is perhaps about the definition of wage moderation or wage restraint. So what does it mean, wage moderation? Whether there is wage moderation or a wage restraint depends only on whether the development of wages per employee or wages per hour in one country correspond with the development of productivity per employee or per hour in the same country (cost neutral development) plus the inflation target of the ECB (cost and inflation [target] neutral development). If the development of wages per employee is falling below the development of productivity per employee plus the inflation target of the ECB there is by definition a wage restraint or wage moderation. If the development of wages per hour is falling below the development of productivity per hour plus the inflation target of the ECB there is by definition a wage restraint or wage moderation.

If every country in the EMU would have sticked to that rule there would be neither unfair competition by squeezing wage development below productivity development nor any lack of demand by the wage squeezing country. There would be also no inflation rate that ranges so far below the inflation target of the ECB as we observe it now for a fairly long time. In contrast, “a convergence of member countries’ production, employment, and trade structures”, as Storm argues, is neither realistic nor necessary to make a currency union work.

So, Storm may be right to criticise economists which are too narrowly focused on ULC and therefore forgetting other circumstances – e.g. the banking system – which are decisive to explain the crisis, too. However, he doesn´t seem to understand the meaning of nominal ULC in that debate and for the EMU, too.

Dieser Text ist mir etwas wert

|

|